Assessing speech & language needs

10 tips for assessing speech & language needs in children with PDA

by Libby Hill, Speech and Language Therapist

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a profile on the autism spectrum. As its name suggests, people with a PDA profile avoid demands to an extreme extent. Not in the way that all of us sometimes avoid demands, but in a way that is underpinned by huge anxiety, drives a need to be in total control and makes ordinary everyday things extremely difficult. These ordinary everyday things include appointments with speech and language therapists, of course!

I’ve assessed over 100 children with a PDA profile, and not one of them to date has had typical language and social communication (likewise adults with PDA, or PDAers as many preferred to be called, report exactly the same issues).

This isn’t surprising, of course, given that PDA is a profile of ASD. But with PDA the speech and language difficulties often present differently. Many children with PDA are extremely articulate, and many of their parents wonder how an SLT could possibly be helpful for them. By building an accurate picture of strengths, as well as understanding where some underlying difficulties arise from, we can help all those living and working with children with PDA to implement effective strategies and enable these, often very bright children, to maximise their potential.

What is PDA?

This is a quick overview of the main features of PDA:

- Resisting and avoiding the ordinary demands of life

- Using social strategies as part of the avoidance

- Appearing sociable on the surface but lacking depth in their understanding

- Excessive mood swings and impulsivity

- Being comfortable (sometimes to an extreme extent) in role play and pretence

- Language delay, often with a good degree of 'catch-up’

- Obsessive behaviour, often focused on people rather than things

Of these features, numbers 3 and 6 are the most relevant for SLTs.

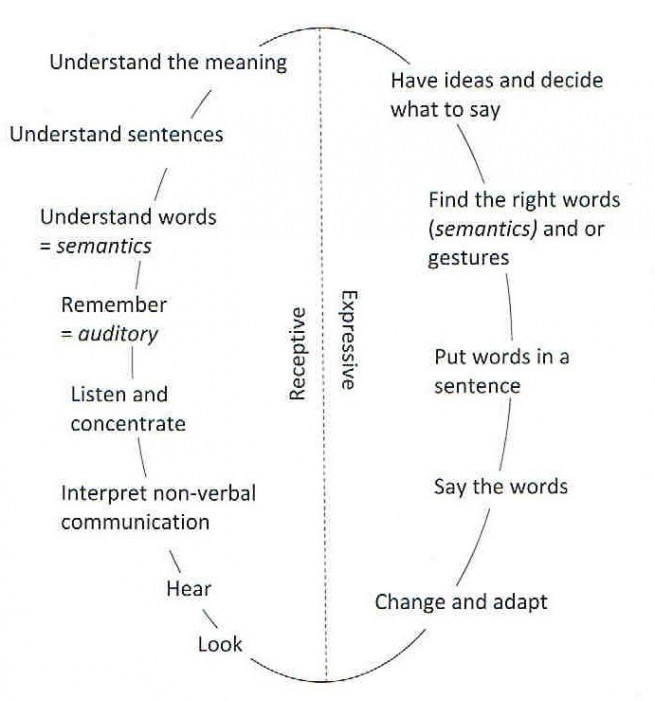

Children with PDA have sufficient language skills to be able to mask, argue and ‘manipulate’ (to the degree that their avoidance often uses social strategies such as distracting or giving many reasons why they aren’t able to comply). Their language and communication skills are also enough to be fully aware that they are struggling, which increases their already heightened anxiety. And, communication is a demand in itself, of course! As the Communication Chain reminds us, there are so many steps involved in the process that it is easy to see how overwhelming it can be especially when, as with most people on the autism spectrum, PDA children also often have slower processing speed.

Top Tips

You may be called upon to assess a child with an existing diagnosis of ASD with a PDA profile, or you may be working with a child as part of an autism assessment, or you may have no advance information about a child’s presentation. However if PDA is a factor, you will quickly notice that your usual approach might not be effective.

Children with PDA might

- pretend/hide/disguise their difficulties and use a wide range of reasons why they can’t engage with you

- distract verbally or physically, which may include an element of trying to ‘shock’ you

- get angry, with themselves, with you or with objects in the room

They might equally be charming, funny, inquisitive, creative and passionate!

Over the years I’ve assessed and provided therapy for many children with PDA. Initial assessments can be straightforward, as many children with PDA often enjoy novelty. However follow up therapy can often prove trickier. Along the way, I’ve learned a few strategies that can help encourage a child with PDA to engage:

- Keep calm, be ready for anything and don’t take it personally – always remember that behaviour, however ‘outrageous’, is underpinned by anxiety and a drive to avoid a stressful situation. One 10 year old child told me I couldn’t assess him because I hadn’t had sex with his Dad! I just shrugged and said “No, well, I’ve been a bit busy!”

- Keep ‘rules’ to a minimum and pick battles carefully. For instance, I only have three rules: no hurting themselves, no hurting me and no damaging property. Beyond that, I just go with the flow.

- Provide choice as much as possible as this will help children to feel in control. Choice over which room to use (or even to go outside), where to do the activities (on the floor, under a table …), which order to do the activities in, even which assessments to use.

- Use indirect language to lessen the perception of demand. So instead of saying “We’re going to …” or ‘It’s time to …” or “You need to …” try saying “I wonder if we can …” or “Shall we see whether we can beat the clock …” or “Maybe we could investigate …”.

- Allow lots of time – plant a seed of what you’d like to happen at the start of the session but don’t expect it to happen straight away.

- Follow the child’s lead and interests – both as a way to engage and as something to structure activities around, but also as a way to make demands more indirect and get children on board. One little boy I worked with used sound bites and little scripts revolving around zombies and teleportation as the basis of his expressive language. When he angrily ordered me out of the room part way through a session I crept out and then burst in through a different door telling him I’d teleported! He forgot he was cross with me and we were able to continue.

- Use humour – this often works wonders and is a great way to reduce tension. Make jokes, put on a silly voice or use an exaggerated facial expression or feign ignorance. Don’t worry what anyone else who may be observing may think … you’re doing whatever the situation demands and focusing on the end goal by whatever means necessary.

- Use distraction – another great way to diffuse anxiety and lessen the demand. When the little chap I mentioned earlier ran outside and refused to return, I got down on all fours pretending to be a horse and said “hop on, I’ll save you from the zombies!” and we happily piggy-backed back inside.

- Add fun activities into the mix like blowing bubbles or blowing and letting go of a balloon as a way of reducing anxiety and allowing a ‘pause’ in the proceedings. Or incorporate these activities into your assessment/therapy - I have on more than one occasion assessed language whilst colouring in a picture side-by-side with a child. I also find my wonderful co-therapist Ralph the labrador very helpful in this regard.

- Remember that what works one day might not work the next, so be ready to mix it up and always have plan B up your sleeve!

Conclusion

Difficulty with language processing and social communication adds to the already very elevated anxiety levels in children and adults with PDA. By being compassionate, adapting our approach and always remembering the old adage of ‘the children who need the most help often ask for it in the most unhelpful way’, we can make a real difference.

‘I wonder …’ – a mini case study

F is a beautiful, funny, witty, gorgeous little princess who is like a ray of sunshine. Until you ask her to do something, when she can turn into 'a monster from your worse nightmares' (parental quote, not my words!). A session with F might go something like this:

Me: 'Ok, thank you for choosing the order of the session F, let's see, you chose the memory game first.'

F: 'yes, but I'm not doing your stupid game now........I'm playing with the plastic fruit'

Me: 'No problem, let's use the fruit for the game.'

F: 'Ok, but I'm not playing on the table.'

Me: 'No problem, let's sit on the floor to do it, we'll have more room anyway.'

F: 'NO and you can't make me!'

Me: 'Where shall we do it because look, (pointing at her written list) you said we'd do it and it's on the list?'

F: 'On the floor under the table.'

Me: 'No problem!'

This might happen for all 4 four activities or we may only manage two!

One day I hit on the power of “I wonder”. I didn’t tell her to do anything at all. I acted as an equal, discussing her favourite things, commenting on her new shoes, drawing on a white board next to F drawing on her white board. I asked no questions but made lots of comments:

'I wonder where F would want to work' (she chose somewhere different to usual)

'I was wondering what F had for Christmas’

'I wonder what order we should do these'

'I wonder if F could show me'

'I wonder if F wants to carry on drawing while we do this activity'

'I’m wondering what to do here...'

'I wonder whether I could have some help with this...'

We managed all the activities and both of us looked far less stressed at the end.

I decided to try this approach again, though remembered that F may have moved the goalposts by next week!

Libby Hill has been a speech and language therapist for over 30 years, specialising in children and young people with autism. For more info about Libby Hill please see www.private-speech-therapy.co.uk